(click image to enlarge)

‘A Times newspaper journalist recently said to me during an interview with me about my veteran portraits, “You know you’re giving these war veterans therapy don’t you?”. I hadn’t realised before and it was never my intention to do so, that was not the motivation behind the project, but since he mentioned it I’ve come to realise that he may be right.

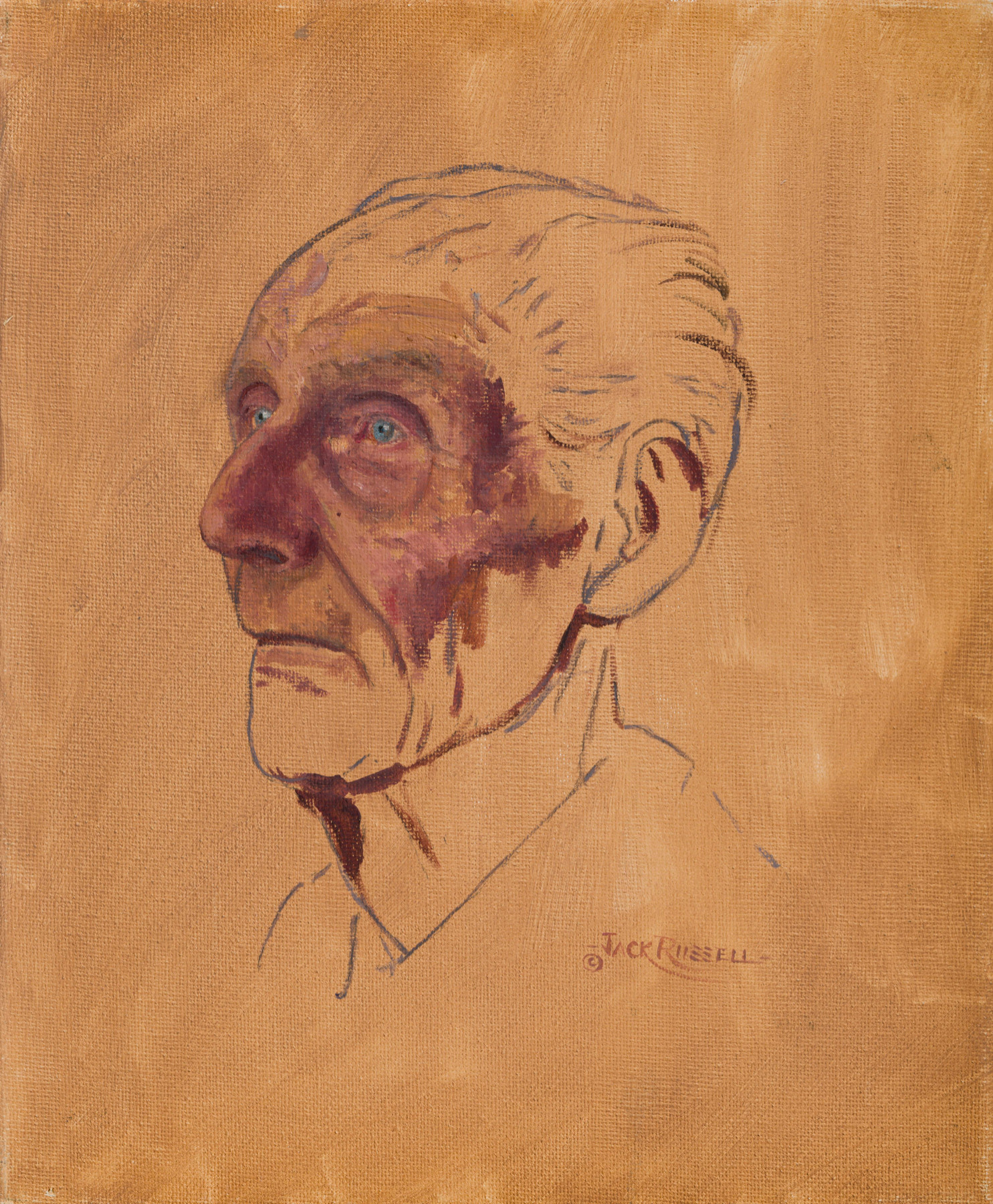

My portrait of Joe Collett is a prime example. He was part of my self-imposed challenge to paint the last surviving members of the Gloucestershire Regiment who fought at the famous Battle of the Imjin River, Korean War, 1951.

(My driving instructor was there, that’s how I became interested in that particular battle). The regiment were surrounded for several days by tens of thousands of Chinese soldiers until eventually most of the regiment were either killed or taken prisoner. A few escaped back to friendly lines but not many. Two Victoria Crosses were awarded for the action. Joe Collett was there. He was wounded in the hand and legs early in the battle and was evacuated back to friendly lines in an ambulance. All the other veterans who I painted from the battle were eventually taken prisoner. This has always troubled Joe. He has always felt extremely guilty that he survived and got out before it was too late. Many of his friends were killed or captured. When I wanted to paint him, I was told that it may not be possible, he may not agree. I learned that he wasn’t really one for regimental reunions and didn’t like doing interviews. He pretty much kept himself to himself. But he is a sports fan, in particular cricket and football. So when he heard that it was an ex-Gloucestershire and England cricketer who wanted to paint him, he agreed to do it. The veteran portraits are normally for me two sittings. The first sitting is short. Just a chat and a few photographs (for reference). The second is much longer, around three hours, where I paint a small colour sketch to take back to the studio as reference for the larger, final portrait. Joe was very accommodating but you could tell he was very wary of the whole situation and wasn’t overly conversational when it came to chatting about what happened at the battle. I could see it was difficult for him to go back there in his mind.

I took the necessary photographs and left him in peace. During the second sitting, while I was painting the colour sketch, he slowly opened up and began explaining, gradually, in more detail, what actually happened. I was so engrossed in what he was saying that I hardly painted at all for a while and just let him release all that hidden information. Information he had kept to himself for 70 years. I could see how difficult this was for him. It became even more difficult when he began to talk about his son who had also served with the army, this time in the Grenadier Guards. The reason it was so difficult was because his son was no longer alive. I could see the pain and torment in Joe’s face as I painted him. The anguish in his eyes. After a couple of hours I stopped painting and left the colour sketch unfinished. But to me it is finished. Because once I had captured that look of pain in Joes eyes

I knew I had captured the very essence of what I was after. When Joe stood up again at the end of the sitting he seemed to stand taller than before. He even began to show a smile for the first time. He looked much more relaxed. More at peace. In fact his demeanour has changed considerably. We even joked and laughed about the world in general. It was an amazing transformation. So much so that in the final portrait, although there is still a little anguish in Joe’s eyes, there is a hint of a smile. A man in a better place. To totally appreciate the look in Joe’s eyes in the colour sketch you need to have heard the whole story from him first hand. To hear the outpouring of pain to really understand that look in his eye. But the emotion is there. The pain of guilt and grief. Guilt that he got out of the battle early and was forced to leave his mates to die or suffer the 2 years depravation of a Chinese prisoner of war camp. And grief for the loss of a son at such an early age. I’ve met Joe several times since at various regimental reunions and get togethers. The scars are still there but he is now someone more at peace and with less weight on his shoulders. There’s even a joke and a smile from him from time to time. The driving force behind painting war veterans for me is simple. To make sure that what they went through, their sacrifice, is never forgotten. It’s as simple as that for me. Capturing their character on canvas is the best way I know of making sure that happens. After we are all gone, the portraits will still be here. Caught on canvas forever.’

Jack Russell MBE